Report by Whatsy

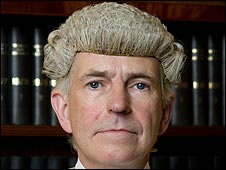

Lord Bracadale, the presiding judge in the case, began his summation by directing the jury that "only they and they alone" could decide on the facts of the evidence, and that there were some particular consequences of this for this case. Lord Bracadale informed the jury that although the case involved Socialist politicians, their political views should not matter to the jury, whether they agreed or “vociferously disagreed” with them.

Lord Bracadale directed the jury that this was “not a court of sexual morals”, and neither was it about the morality of telling lies, and that the jury's task was to decide whether the accused had lied in court under affirmation.

Lord Bracadale continued that the jury should put out of their mind any sympathy they may have, and that the consequences of conviction on the accused should be put out of their minds as it was “not a matter to fix your judgment on in any way”, as this was a matter solely for Lord Bracadale himself.

Lord Bracadale described how the jury could draw inferences from a number of pieces of evidence, and that they had to bear in mind the credibility and the reliability of witnesses, describing these as separate – with credibility implying the witness was telling the truth, and that reliability implied that the witness was attempting to tell the truth as best they could, but that this may not always be reliable.

Lord Bracadale stated that the starting point of evidence from witnesses should come from the witness box, and that police statements could be used to jog witnesses' memories or they could be asked to agree with them. When assessing a witness's credibility and reliability, Lord Bracadale gave the examples of

- demeanour

- tone

- consumption of drugs & alcohol at the time of the event they were recalling

- consistency with other evidence you do accept

- comparison between a witness's testimony in court and police statements

- juror's own common sense and experience of the world

as valid ways to test the quality of the witness's testimony.

Lord Bracadale also stated that if a witness refuses to accept the contents of a question, their response was not evidence, and that anything he himself said about evidence was not intended to show his opinion of that evidence.

Lord Bracadale told the jury that their recollection of evidence was what mattered, and that the level for reasonable doubt they may have would be something that “real doubt that would cause you hesitation, to pause, in your own life”, and should not be a fanciful level of doubt or a level of mathematical certainty. Regarding evidence, Lord Bracadale stated that it was not necessary for every piece of evidence to be corroborated, just that two pieces of evidence were required for guilt, and that the burden of corroboration lay with the Crown, not the defence, who did not have to prove anything.

Lord Bracadale stated that evidence from deleted charges on the indictment was still available to the jury to consider if it is useful, and that it was normal for some charges to be dropped in the course of a trial, as the Crown had to give “Fair Notice” of charges, even if evidence does not emerge to corroborate the charge, such as with the Subornation BeanScene chapter involving Colin Fox.

Lord Bracadale clarified that the charge of perjury required the jury to agree that Mr Sheridan gave willfully false evidence during the 2006 civil trial – that he knew his evidence was false at the time.

At this point, Lord Bracadale declared the court should adjourn for lunch.

On resumption, Lord Bracadale reiterated to the ladies and gentlemen of the jury that the Crown needed to prove beyond reasonable doubt, with evidence from more than one source, to obtain a guilty verdict on any of the six charges.

Lord Bracadale then proceeded to give a detailed summary of each remaining charge subsection and the witnesses and evidence relevant to each. These have not been included here in the interests of time, effort, accuracy and repetition.

After dealing with each charge & related evidence in turn, Lord Bracadale made a specific mention of the “McNeilage Tape”, instructing the jury that they must only take into account the evidence of witnesses when assessing this particular piece of evidence, and that the jury must not do their own detective work to decide whether they think it sounds like Mr Sheridan.

Lord Bracadale concluded by describing how the jury would reach a verdict, from the three available of Guilty, or both acquittal verdicts Not Guilty and Not Proven, instructing them that a majority of the original count of fifteen jurors would be required to find the accused guilty, meaning eight jurors would be required to find Mr Sheridan guilty to convict him of perjury on each of the six remaining subsections of the remaining charge. If they found him guilty on some of these subsections but not others, they should return a guilty verdict “on deletion” of the charges which they did not find the accused guilty. If all subsections resulted in less than eight guilty verdicts, the jury should return a Not Guilty verdict.

The revised indictment listing the relevant sections that Mr Sheridan can be found Here

The revised indictment listing the relevant sections that Mr Sheridan can be found Here

With that, Lord Bracadale asked the jury to return to their room to consider their verdict and court was adjourned.

No comments:

Post a Comment